A Treatise On Code: Scale

In May of 2007, Facebook deployed what would likely be the single greatest catalyst to their eventual domination of the “social networking” industry, the Facebook Platform.

Outside of internet technology enthusiasts and a mere 20 million Facebook users, the event was insignificant. Yet for a small set of entrepreneurial engineers, it marked the first internet gold rush since the original internet bubble.

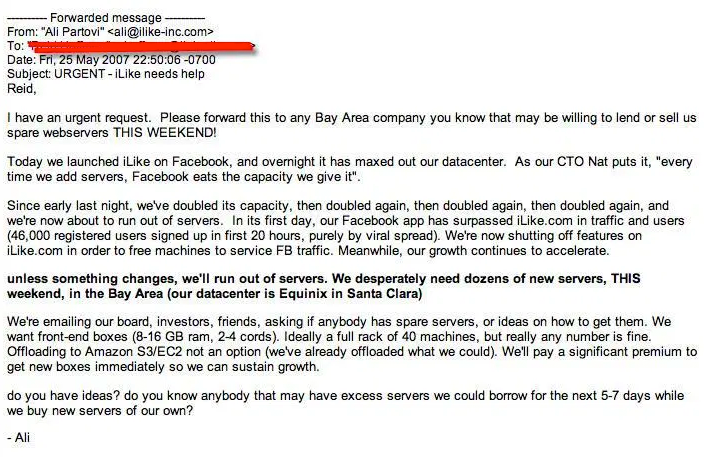

An early indicator of the massive opportunity came in an email from Ali Partovi, CEO of iLike, an application that was poised to be iTunes of the Facebook platform. The email, which quickly circulated the technology blogs, was a desperate cry for help from Partovi. The company was in dire need of additional servers.

For any consumer facing application, this is phenomenal signaling to investors that the company clearly has found product market fit. While most will never experience such overnight demand, one thing is certain: scaling issues are never planned.

When Scale Hits You In The Face

Unless you are building a new technology infrastructure service, scale is something that is typically forced upon you.

A server runs out of memory, a database exhausts it’s connections, a job queue balloons beyond a manageable level, or some stray bug in the code results in a massive hit to the bottom line.

For all non-robots, it induces panic.

In this moment, what follows is a sequence of thoughts and events.

First up is a series of expletives. These typically come from an executive who’s cursing about the site not working. If you happen to be the technology leader responsible for managing things, you too will be cursing soon after.

What comes next is a moment of intense focus. Initially we kill processes that are hogging resources. Then we figure out if there are any dials we can turn that will buy us time. This is the throw money at the problem stage.

Given that we now live in a world of cloud services, money will actually get you pretty far since everything is run on commodity infrastructure. It’s a solid short-term solution.

However the greatest irony to a technology leader being crushed by scaling problems is that code alone cannot scale.

Don’t get me wrong, acute errors can mostly be resolved with technical solutions. Yet when scale appears, it forces a magnifying glass upon the organization.

All the poor strategic decisions that were made up until now spill back out into the open. It’s from within those deep and exposed wounds that we find the next stage of our story.

Built To Scale

One of the most common issues found in rapidly growing software organizations is the absence of structural procedures. When a team is comprised of a few people, it’s easy to plan things.

This is compounded by the strategy I concluded in my last article, “Code as quickly as possible, not in a way designed to scale”.

Now that scale has arrived liked an avalanche, the strategy has to pivot on a dime. Technology managers move from an obsession with code to, hopefully, a passion for people and processes.

So if this series is about “the right way to code”, what does this phase mean for our growing code base?

If you guessed “people and processes”, you’d be right! This materializes in the code in a number of ways.

From Humans That Code To Coding For Humans

Let’s start with the most obvious code situation at this point: technical debt. As a company thrashes with their product and output code in a rush to reach product market fit, technical debt is rapidly accrued.

At the beginning this debt can be viewed as a form of strategic financing. Combined with capital, it provides leverage for a small set of ambitious engineers.

However warning signs will begin to appear. New engineers take a while to onboard. System performance degrades. New feature development slows despite encouraging words from founding product managers.

All of a sudden the technical debt becomes too big to ignore and resources are quickly allocated. So what are the guiding principals at this moment in time?

Before sharing the first principal, I’d like to draw on a favorite and controversial quote from Phil Karlton:

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

While it feels pedantic to debate the names of variables and classes, it is of the utmost importance.

This is effectively illustrated by Martin Fowler in his book, “Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code”. In it he states:

The compiler doesn’t care whether the code is ugly or clean. But when I change the system, there is a human involved, and humans do care. A poorly designed system is hard to change—because it’s difficult to figure out what to change how these changes will interact with the existing code to get the behavior I want. And if it is hard to figure out what to change, there is a good chance that I will make mistakes and introduce bugs.

All the early engineers who were present for initial architectural decisions already have a deep understanding of how things work. They don’t have a problem with navigating the code base. However each new developer that’s onboarded will struggle to ramp and contribute quickly.

So how does a team offset this? The simple answer is to begin cleaning things up. Simplifying the code through SOLID design principals is a great start.

Yet companies don’t need a simple how to article. They need the first rule of creating great code at scale: Institutionalize best practices centered around developer productivity.

This typically materializes in many ways including:

- Engineering team metrics (velocity, etc)

- System performance monitoring

- Internal training sessions

This cannot be driven from the bottom. It must be something that leadership is bought into. If engineering leadership isn’t, the company won’t die but will likely destroy development velocity.

This is solely due to the fact that business leadership will wonder why things are taking forever and throw more money at the problem.

From Shouting To Proactive Communication

So why does this money only exacerbate issues? Brooks’s law, as defined in the book, “Mythical Man Month”, effectively explains this:

“Communication overhead increases as the number of people increases. Due to combinatorial explosion, the number of different communication channels increases rapidly with the number of people. Everyone working on the same task needs to keep in sync, so as more people are added they spend more time trying to find out what everyone else is doing.”

In other words, more people means more channels of communication. While the early engineers could yell across the room at each other, that approach no longer works.

Not only is it harder to organize people but as things scale there will also be an increasing void of leadership. While vision and mission are great at the beginning stages of a company, they are not responsible for launching success.

Instead, the organization built something that fulfilled a need or desire of a specific market, vision be damned.

Yet now with more employees (brought on in part by the “throw money at the problem” strategy), more people will look toward leadership for answers, and more importantly, security.

Why security? Things are changing! Code will break, early employees may leave (voluntarily or involuntarily), new organizational structures will be developed and disbanded, and things will seem uncertain.

For the engineering and product teams, that uncertainty will be apparent. So how do we create great code in this environment of uncertainty? With great communication.

So here are my key rules of communication that will lead to “great code”:

- Clarity of purpose - It’s easy to become disconnected from the end users of our products. As engineers we are focused on solving technical problems, not people problems. This is why it’s key to remind all team members of scaling organizations about why they are there.

- Transparency - Given the feeling of instability, it’s key that the team feels as though they have visibility. People don’t want to necessarily solve all the problems, they just want to trust that those problems are being dealt with. Early scaling issues break that trust which is something that transparency helps to rebuild.

- Consistency - This means that you should have a consistency spokesperson on a consistent basis providing the information that team members need to know.

These principles are utilized at all levels of management. From the CEO on down to the engineering manager.

From Code Issues To Human Ones

So if this series is about “code”, why did this article go so wildly off the rails into one focused on management and communications?

The reality is that at scale, great code is produced by great teams. Great teams are managed by great leaders. Great technical leaders are focused on one thing: maximizing developer productivity.

For those who follow this maxim, scaling issues of the past will only be that: the past.